Ring Around the Sun & We Rage On

13 November 2025 - 10 January 2026

Alma Pearl, London, UK

‘When a word appears,’ wrote the French psychoanalyst Anne Dufourmantelle, ‘a world is born with it.’ Dufourmantelle is referring to the word secret, which first appeared via Latin in the twelfth century. By designating something hidden, the secret doesn’t just describe the world as it is, but forges something new and powerful within it while at the same time containing the seeds of undoing. The secret is the eye of the storm, a hurricane that can upend everything around it while remaining, at its core, hidden from view. In its earliest iteration the secret referred to the separation of a harvest’s good grain from the bad; from there it extended into other kinds of setting apart: private letters, closed boxes. Later it came to designate parts of the body hidden from public view, and it was this hiddenness, Dufourmantelle wrote, that bestowed on the secret its erotic valency.

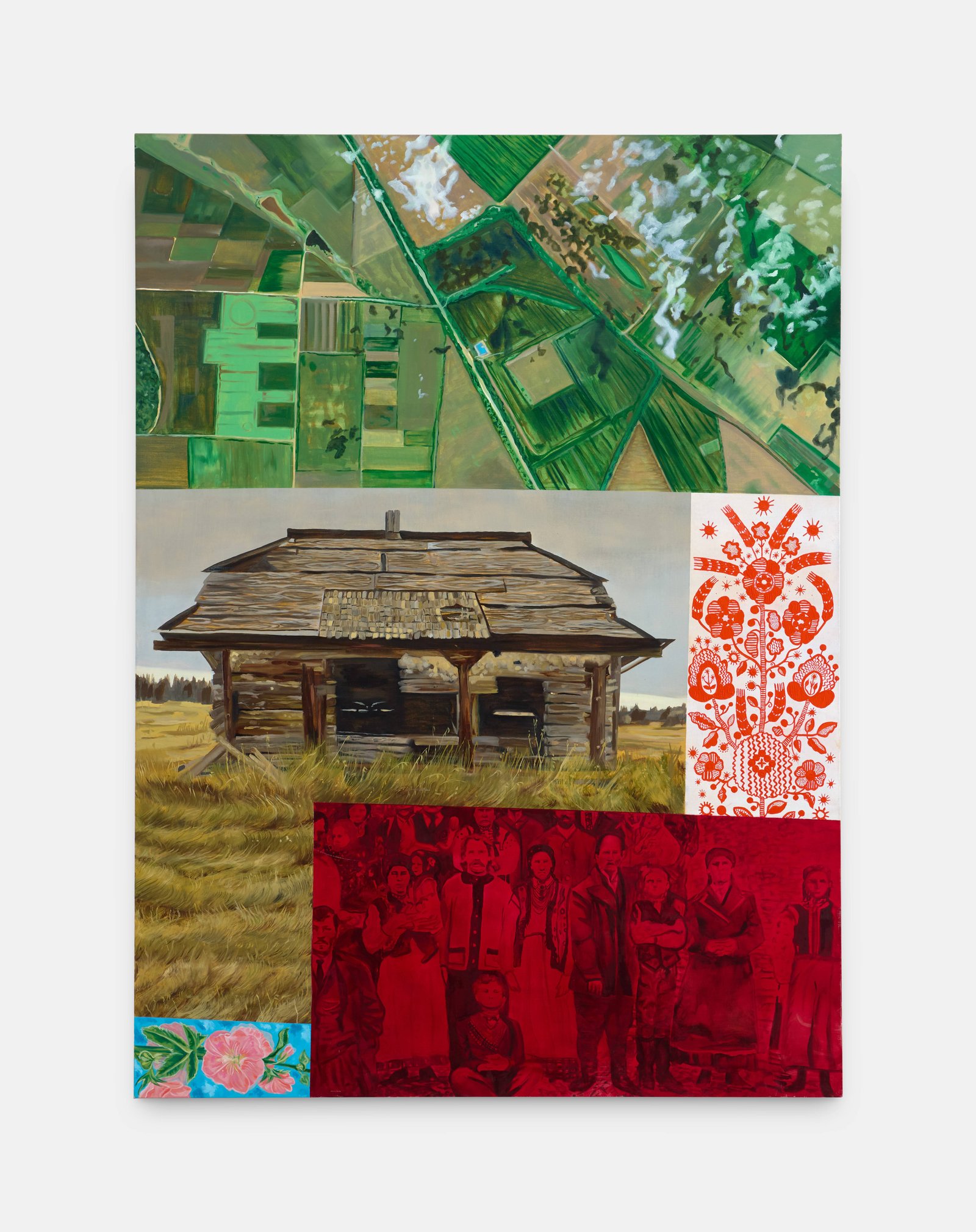

These potent and paradoxical aspects of the secret – generative, obliterative and erotic – animate the constellation of works in Ukrainian-Canadian artist Ayla Dmyterko’s Ring Around the Sun & We Rage On. Spanning oil painting, sculpture, moving image and a collaboration with theremin player Christina Masha Milinusic, the works gesture to folklore and cultural stereotypes of Eastern European and Slavic heritage, from the Old Believer communities to Cold War tropes of the Soviet ‘spygirl’. Taken together, the works propose identity less as something identifiable and cohesive, and more as debris left in the wake of a tornado – a phenomenon that is simultaneously a force of destruction and one that forges a way across a terrain, rearranging everything it touches.

The spiral of the hurricane lends choreography to the exhibition, which is loosely organised as a concentric circle. At the outer fray lies debris, artefacts and ephemera that have been picked up and deposited by the storm. Here are motifs that recur throughout Dmyterko’s work, cultural memories that repeat on the children of those who have emigrated, half-remembered stories and objects. Ceramic hollyhocks symbolise home, their stems woven into tactile and talismanic ribbons and loops. Wooden distaffs – spindles on which women sat in circles to spin wool and gossip – recreate the spatial dynamics of the secret. Here the circle is conceived as both intimate and a protector of the unknowable: the outer face of distaffs were often painted to intimidate and show off one’s skill to those sitting opposite, while the inner face bore a mirror for personal reflection.

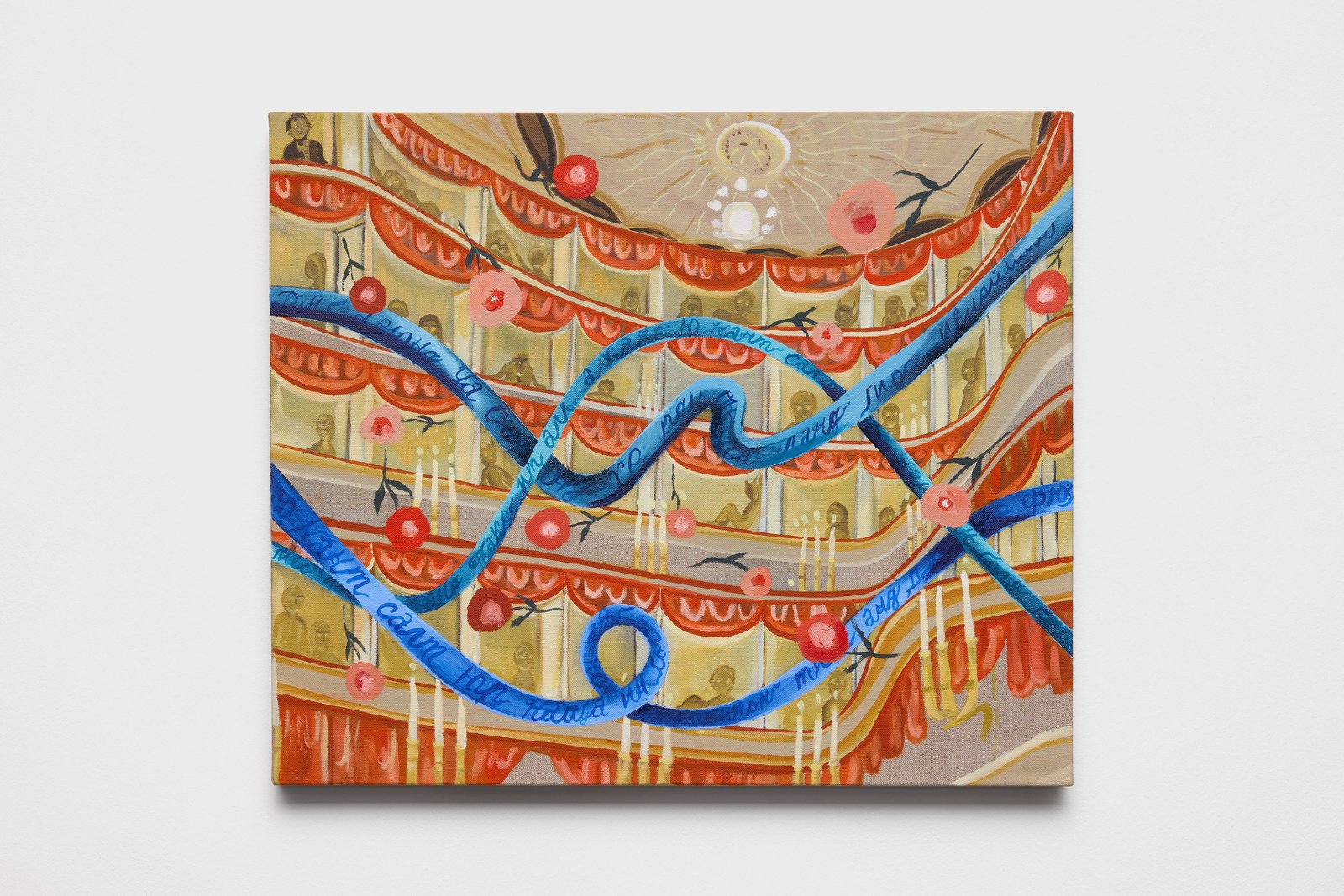

In Slavic Old Believer communities, it was understood that the air itself was thick with demons, which were small enough to fit in one’s pocket and wild enough to roam the fields outside. The only way to keep oneself free of the demons’ grasp was to keep in constant motion – something akin to the devil makes work for idle hands. In this sense, to spiral is not just to spin out or lose control, but to perform a tactful dance with risk and change. As well as in the spiralling hurricane of the exhibition’s layout, this dance is evoked through the recurrence of ribbons and umbilical-like cords. In the series of paintings Caim I-VI (2025), ribbons contort across the canvases, each one linking to the next as if to bind the air between them. The ribbons are the movement and costumes of the dancer, but they are also her spinning gaze as she performs. The paintings are a kind of negative voyeurism, depicting empty theatre stalls in Moscow, New York and Paris – all places where the Bolshoi Ballet performed before the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In keeping with Dufourmantelle, who is a key touchstone for Dmyterko’s thinking, the ribbons are emblazoned with unreadable phonetic incantations.

Two large-scale paintings, The Middle Distance and Circles of Confusion (both 2025), also demarcate the tornado’s outer space. In The Middle Distance, hurricanes appear as sentinels marking the way ahead, ambiguously protective or policing. The painting’s format borrows from colonial propaganda posters from the early twentieth century which promoted emigration to Western Canada. These depicted the false promised land of immigrant life: stable income, education and bucolic plenty, typically featuring attractive young women, beneath which lurked the secret of indigenous peoples’ displacement. In Dmyterko’s painting a figure struggles to gain footing on this supposedly smooth path, echoing the treatment of those who, like Dmyterko’s ancestors, did make the move from Eastern Europe to Canada, only to be treated, as recently as the Cold War, as potential ‘enemy aliens’.

Similarly, in Circles of Confusion, a young woman lies – or has possibly collapsed – at the beginning of the path. She is drawn from Andrew Wyeth’s famous painting Christina’s World (1948), her facial features adapted by Dmyterko to match those of Eastern Orthodox icon paintings. In the distance, ghostly prairie houses rise up into the air, held aloft by the storm. Are we observing a figure setting out from her syncretic cultural origins, or an attempt to make her way back to something lost? The painting’s title suggests that it is both at once, suspended in an impossible dance. Blue curtains frame the scene to remind us that what we see is a performance as much as a journey, and that Dmyterko’s figure, who gazes back, is all too aware of her bathetic circumstances. Like the ‘spygirl’ character who recurs throughout the exhibition – incarnated by the artist herself in the video work SK Eye (2025) – Dmyterko’s female figures play with absurdity and concealment to subvert colonial and Cold War paranoia, transforming these stereotypes into tools of psychic survival.

In the eye of the storm there is calm, the domain of secrecy. The gallery’s inner room contains a projection of Ukrainian circle dancers. Unlike watching a performance on stage, the viewer finds themselves imbricated in the middle of the dance; they are reminded that movement is ongoing, perhaps even literally – of those forced to immigrate today due to the ongoing invasion of Ukraine. A sound work made in collaboration with a theremin player binds the air of the space; Dmyterko likens this instrument to painting, since both involve forging something from nothing, an attempt to ply the frequencies of the air. Like the static that augurs the onset of a storm, the works in Ring Around the Sun & We Rage On are attuned to such frequencies, the secret codes of air, genealogy and memory. They know that the storm will come and will ravage, but they also know that the dance must continue; they cannot afford to keep still.

Text by Daisy Lafarge

Generously supported by the Canada Council for the Arts

The Middle Distance, Oil on linen with beeswax, 150 x 110 cm

SK Eye, Digital video, 14:53 minutes

Circles of Confusion, Oil on linen with beeswax, 150 x 110 cm

Secrets Fall in the Forest, Oil & Distemper on linen in found wooden partition, 90 x 84 x 5 cm

Family Frames, Oil on linen with beeswax, 150 x 110 cm

Money on the fields bakes, but it will not grow, Oil on linen with beeswax in found wooden frame, 48.5 x 42.5 x 7.5 cm

In the darkest nights, remember the sun, Oil on linen with beeswax in found wooden kiot, 44.5 x 31.5 x 9.5 cm

Always Remember Your Home, Ceramic with glaze

Like Fire on Water, Egg Tempera on Carved Wood

Edified Eddies, Oil on Linen in cast bronze frame, 25 x 20 x 5.5 cm

Caim ll, Oil & distemper on linen, 48 x 41 cm

Caim lll, Oil & distemper on linen, 48 x 41 cm

Caim Vl, Oil & distemper on linen, 48 x 41 cm

Caim V, Oil & distemper on linen, 48 x 41 cm

Dance of the Fated Furies, Digital video, 09:50 minutes